Hypermeter is a perceived, metric organization higher than the regular meter (3/4, 6/8, etc.). Typically, each regular measure represents one "hyperbeat" in a "hypermeasure." Quadruple is the most common hypermeter. In quadruple hypermeter, four regular measures combine to create one hypermeasure, but duple (two measures = one hypermeasure) is also common, and triple (three measures = one hypermeasure) is less common. Hypermeasures are typically perceived due to changes and/or repetitions that take place during that span of time. For example, if a passage contains a four-measure phrase and its immediate repetition, the passage can be heard as two, four-measure hypermeasures. Similarly, a four-measure phrase followed by a distinctly contrasting four-measure phrase can produce the same result. Like regular meter, hypermeter tends to be mostly the same throughout a work, but irregular lengths can occur (typically due to phrase expansion techniques). Some pieces may not have a perceivable hypermeter.

Just like beats in regular meter, with hypermeter you can often hear which hyperbeat is happening if you know what to listen for. In quadruple hypermeter, you can listen to the following things:

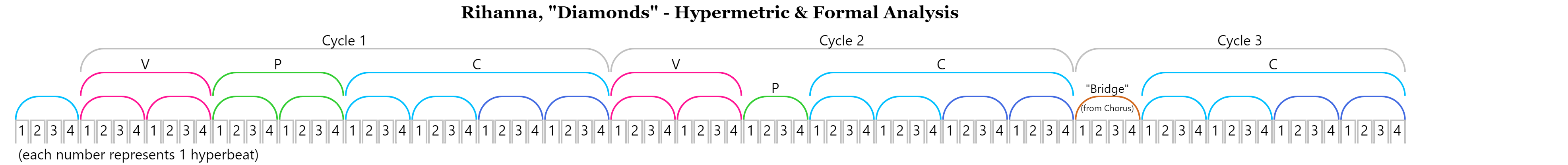

Hypermeter is usually pretty easy to hear in many types of dance music. In Rhianna's 2012 song "Diamonds," you can hear each hyperbeat of the quadruple hypermeter by listening to the chord changes which occur every 1st, 2nd, and 3rd measure (the 4th measure continues the 3rd measure's chord). The harmonic progression is G, Bm, A (which I hear as IV vi V in the key of D major). To hear the actual hypermeasures, pay attention to when the harmonic progression starts over and to the beginnings of textual phrases ("Find light in the beautiful ...", "You're a shooting star I see ...", "I knew that we'd become ..."). In the verse and prechorus, Rhianna's phrases start in the first hyperbeat of each hypermeasure but they don't start on the downbeat of the normal measure. At the very beginning of each chorus, however, her lyrical phrase contains a pick-up that does lead to the simultaneous regular downbeat and the first hyperbeat of the new hypermeasure. Watch and listen to the example below which has the hypermeter labeled for the entire song. Notice that the entire song features a regular presentation of quadruple hypermeter.

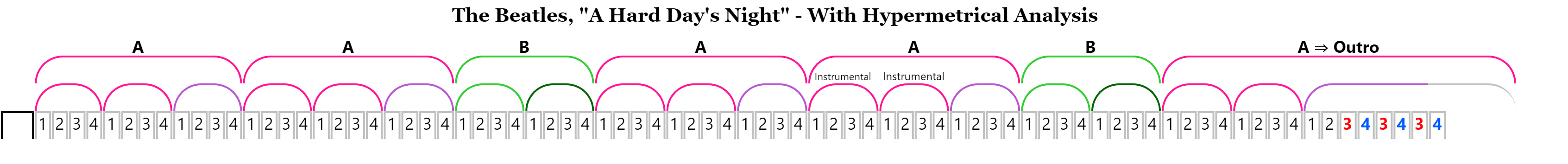

This song also contains quadruple hypermeter. To hear it, pay attention to the beginnings of things. The beginning of each textual phrase ("It's been a hard ...", "But when I get home ...", "When I'm home ..." ) and when the harmonic progression for each phrase begins. The first two phrases of the verse use a I IV I ♭VII I progression (G C G F G) that you can listen for. Notice that the quadruple hypermeter is very consistent throughout except for the very last phrase which has which has the hypermetric counts 12343434 listed instead of 1234 1234. This is where hypermetric analysis veers away from traditional meter. In a hypermetric analysis, you can express a repetition by repeating a hypermetric number. In this case, the music associated with the 3rd and 4th hyperbeats is repeating instead of starting over with the material for hyperbeat 1 (Hypermetric Repetition). To hear this interpretation, compare the last phrase of each A section and pay special attention to the lines that end with "feel all right" or "feel okay." They only happen one time per A section, but in the last one, it keeps repeating instead of moving on to something else like it had been doing. Labeling it 1234 1234 would also have been accurate, but when it's possible to express repetition like this, it's a good idea to do so because it does a better job of capturing the effect of the music.

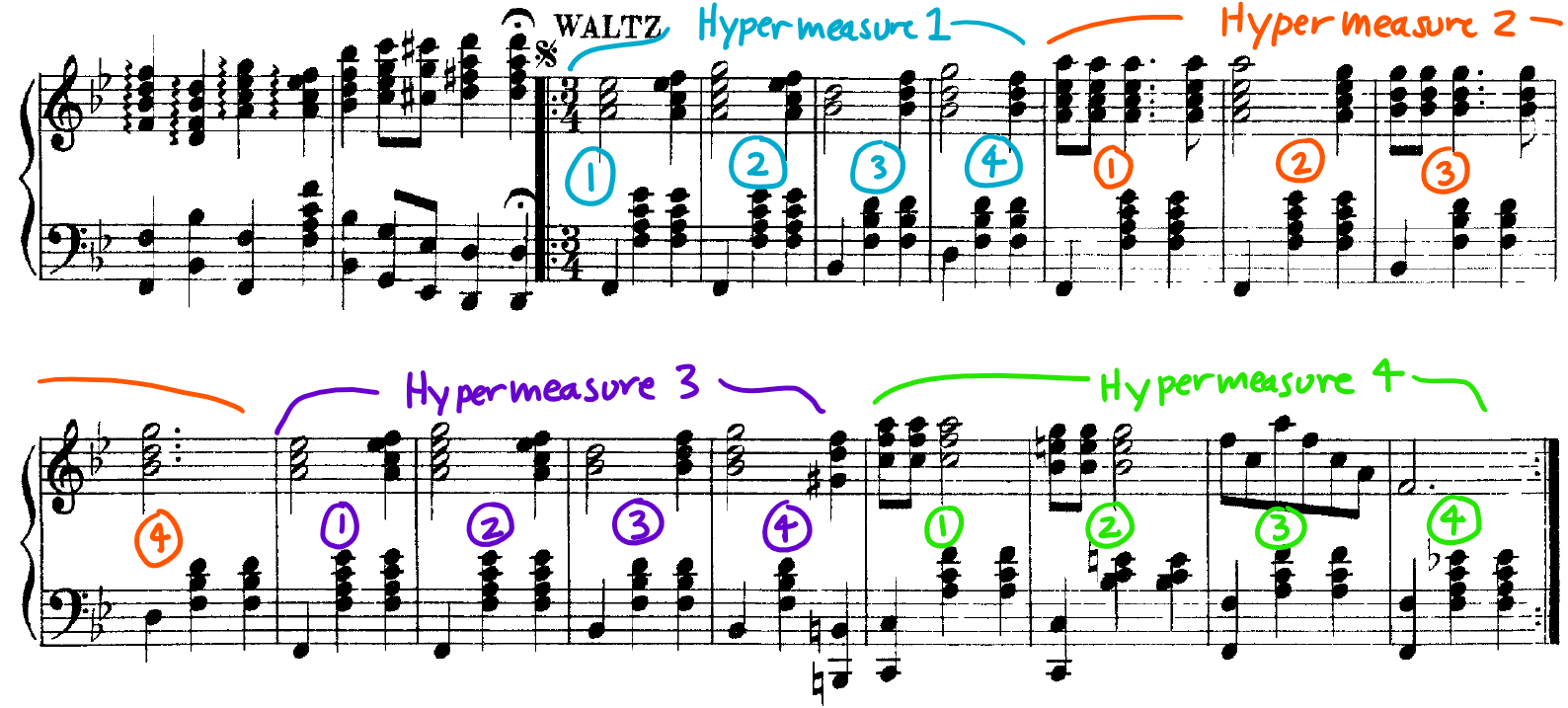

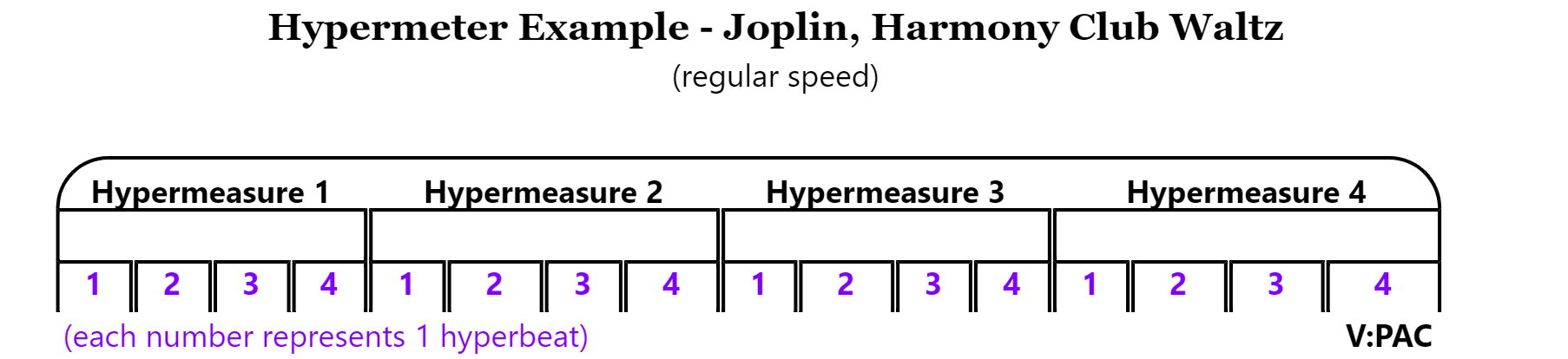

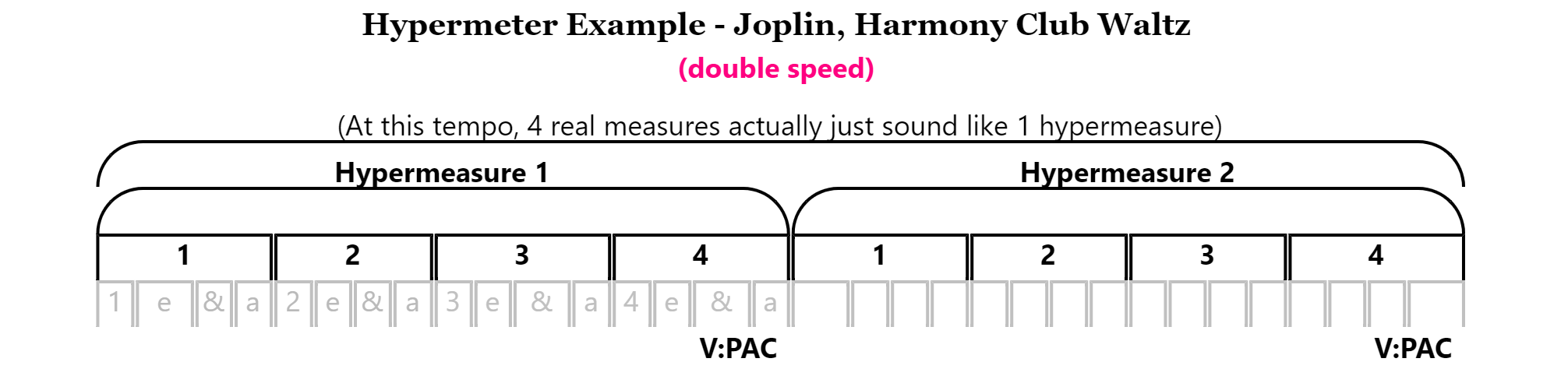

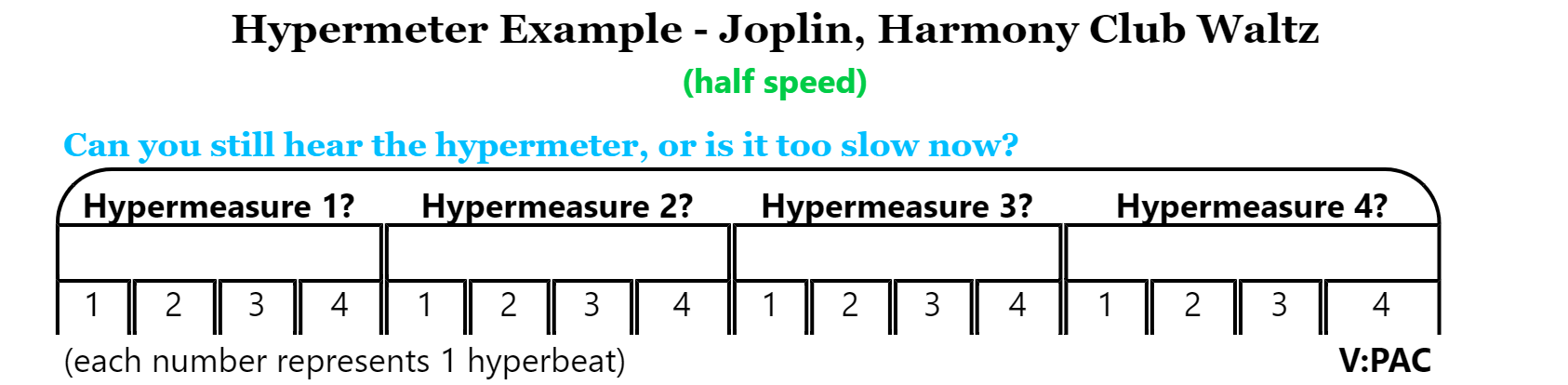

This waltz also expresses quadruple hypermeter. You can see in the score example the normal notation for labeling hypermeter which is to write each count (1234 1234) between the staves and to circle each number. I've also labeled each measure with "Hypermeasure 1", "Hypermeasure 2", etc. but that's not necessary nor common in a hypermetrical analysis, it's just for clarity in this example. Below the score, are the same example at three different tempos. Remember that hypermeter is a perceptible and interpretational phenomenon, and your perception of it can change depending on the tempo. Listen to each of the different speeds below and try to see what meter you hear at each tempo by conducting the meter with your arms. It's likely to be different especially between the double-speed and half-speed versions. The perceptual change you may experience, is just your mind latching onto different levels of meter. If you hear 3/4, you're just hearing the regular meter, but if you hear 6/8 or 12/8, you're listening to the hypermeter.

Mm. 9-16 with hypermetrical counts written between the staves

Regular Speed (Click below to watch & listen)

Double Speed (Click below to watch & listen)

Half Speed (Click below to watch & listen)

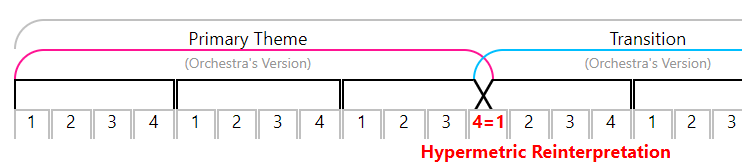

The concept of hypermetric reinterpretation can be applied to say that you think a single hyperbeat is simultaneously doing two different things. Almost always, this occurs at a phrase elision, where the end of one hypermeasure (hyperbeat 4) is simultaneously the beginning of a new hypermeasure (hyperbeat 1). An equals sign is used to show reinterpretation occurred: 4=1. An example of two hypermeasures with reinterpretation would be 1, 2, 3, 4=1, 2, 3, 4. Not all elisions contain reinterpretation

In this example, the end of the first phrase elides with the beginning of the second phrase in measure 12. The music from the third hypermeasure is just like that of the second hypermeasure so use the 2nd one as a model for how the 3rd should go. Listen how measure 12 still functions as the end of the first phrase but the new phrase really takes over, which provides a clear sense of the beginning of a new hypermeasure. Note that the notation 4=1 in the measure where the hypermetric reinterpretation occurs.

Orchestra's Exposition

Hypermetric repetition is an interpretational decision to represent how you think a hypermeasure has been expanded beyond its expected number of measures (from 4 to 5, for example). Applying this technique means you think a hyperbeat or hyperbeats within a hypermeasure has/have been immediately repeated. For example, instead of 1234, you could have 12344, or 3 and 4 could repeat together 123434. This type of assertion is usually most convincing when the phrase in question is a variant of a previously stated phrase because then you can compare the two to make the argument.

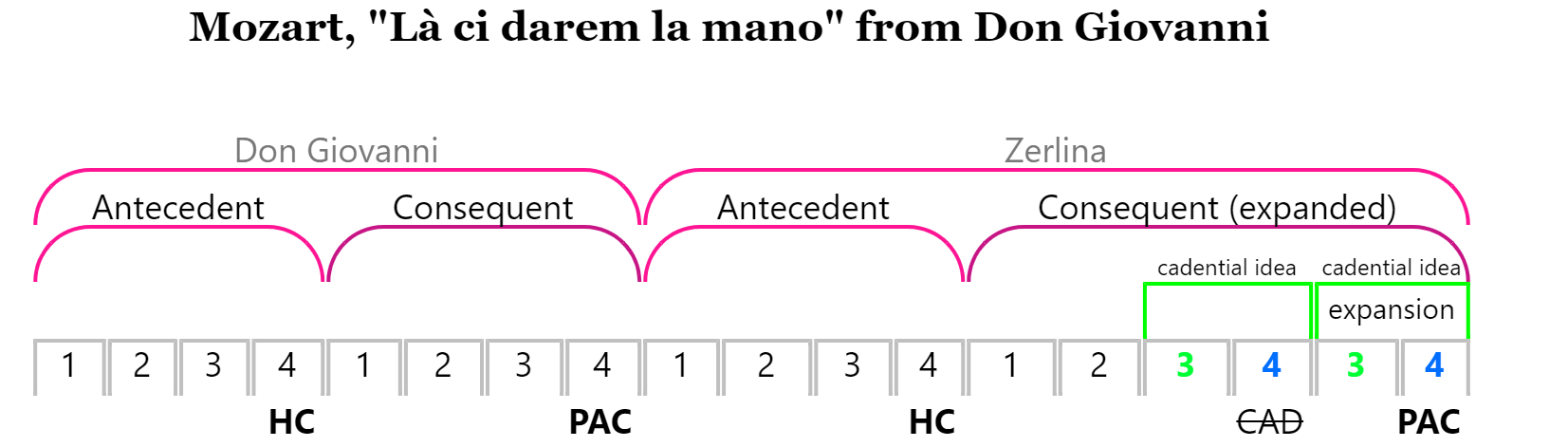

In this duet, Don Giovanni sings a parallel period and immediately after, Zerlina sings essentially the same parallel period (with different lyrics) but this time the last phrase is expanded. Compare Don Giovanni's consequent phrase with Zerlina's. Because we heard Don Giovanni's phrase first, it serves as the model of what Zerlina's will sound like. Zerlina's version then violates our expectations providing a mild musical surprise that extends the phrase from the expected four measures, to six. In the analysis below, I have explained the expansion as a hypermetric repetition where hyperbeats 3 and 4 are immediately repeated. They are slightly varied, but their cadential function and effect remain very similar. I have also crossed out the first attempted cadence by writing CAD to indicate the location of the cadence that was proposed and then rejected in favor the PAC that is proposed and accepted two measures later.

Mm 1-18 (Click below to watch & listen)